This is the first of three stories about the run-up to the 2024 US presidential election in Shasta county, a region of 180,000 people in northern California that has emerged as a center of the election-denial movement and a hotbed for far-right politics.

When Shasta county had to search for a new official to oversee its elections earlier this year, there was an obvious candidate.

Her name was Joanna Francescut, and she had been the assistant elections clerk and registrar of voters in this remote region in California’s far north. Francescut had worked in elections for more than 16 years, oversaw the office of the county clerk and registrar of voters for months after her boss went on leave, and was endorsed by elections officials and prominent area Republicans alike.

Instead, the ultra-conservative majority on Shasta county’s board of supervisors in June selected Tom Toller, a former prosecutor who had never worked in elections and vowed to change the office culture, improve public confidence, and “clean up” voter rolls.

Were it any other California county, the decision would have been shocking. But Shasta county in recent years has made a name for itself as a center for far-right politics and the election-denial movement, which maintains that Donald Trump, and not Joe Biden, won the 2020 presidential election. In the past year, the majority on the board of supervisors, the county’s governing body, has cast doubt on the integrity of the local elections office and sought to rid the county of voting machines.

The move fueled anxiety among some of the county’s residents. Before one of the most turbulent and consequential races in recent history, Toller will be in charge of administering the election to 114,000 voters with just a few months’ experience under his belt.

Already, challenges have been thrown his way. In September, a county advisory board, which makes recommendations to Shasta’s governing body, proposed limiting absentee ballots and returning to one-day voting. Toller rejected the proposal, pointing out the plan would violate state law.

“People are worried about it,” said Robert Sid, a Shasta county conservative who supported Francescut and has been frustrated by conspiracy theories about the elections office. “If there was any hint of scandal [at the office], I’d be the first one down there. But there’s never been anything.”

Toller declined the Guardian’s request for an interview, citing his office’s focus on preparations for early voting.

The controversy in Shasta over the elections office is a more extreme version of an issue that experts have been sounding the alarm about for years. US elections officials are leaving at increasingly high rates after facing intense harassment and threats in the aftermath of the 2020 election and are being replaced by administrators with less experience and institutional knowledge.

For 20 years, Shasta’s elections had been managed by Cathy Darling Allen, one of the only Democrats elected to office in this region where Republicans outnumber Democrats two to one.

Allen’s job, a non-partisan administrative role, radically changed after the 2020 election, when Trump refused to acknowledge his defeat. As an election-denial movement flourished locally and the county’s governing body veered radically to the right, her office came under growing scrutiny and dealt with harassment and bullying. The evening of a local election in June 2022, someone placed a camera outside her office.

Allen was re-elected with almost 70% of the vote that year. But she was frequently villainized by the far-right majority on the board of supervisors, which had set out to dramatically change how elections are conducted in Shasta county.

In early 2023, the county board of supervisors cancelled its contract with Dominion Voting Systems, the company maligned by Trump and his supporters, without a replacement, and attempted to implement a costly and error-prone hand-counting method. Soon after, the state thwarted those efforts with the passage of a bill preventing counties from using manual tallies in most elections.

Far-right county officials insisted they would use their hand-counting method in November 2023 regardless, and falsely claimed elections were being manipulated; Allen made clear she would follow state law, and the election ultimately unfolded without issue.

Many voters heralded Allen’s commitment to upholding election law in the face of unprecedented attacks. People routinely stopped her in public to express their appreciation, she previously told the Guardian, and often sent cards and notes of gratitude. But Allen’s position also made her the No 1 enemy of Shasta county’s far right, one local journalist wrote.

In February, Allen shocked the county when she announced plans to retire with two years left in her term. She had been diagnosed with heart failure, she said. “An essential part of recovering from this diagnosis is stress reduction. As many election officials could probably tell you right now, that’s a tough ask to balance with election administration in the current environment,” she wrote in a letter to the community.

Francescut, Allen’s deputy, seemed an obvious choice for her replacement, given her more than 16 years’ experience assisting with more than 30 elections in the county. She had been training for the role for years and took on Allen’s job – in addition to her own – and oversaw the March election.

She had the support of her ex-boss, elections clerks in two other counties, as well as a conservative former county supervisor.

The board of supervisors held public interviews with eight candidates, including Francescut, Toller and Clint Curtis, an attorney and former congressional candidate who has long claimed he was once hired by a lawmaker to create a software that could rig elections.

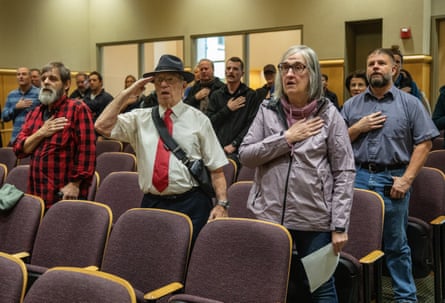

During public comment after the first day of interviews, an air of cynicism hung over the room. Several speakers urged the board to hire Francescut while acknowledging the supervisors had likely already made their decision. “The fix is in,” one woman shouted from the audience.

Board members took a combative approach with Francescut. One supervisor, Kevin Crye, attempted to coax her into criticizing her former boss, while another, Patrick Jones, accused her of “mal-conduct”. Their tone was hostile, said Sid, who characterized the public interviews as a “dog and pony show”.

Francescut, who described the process as “humbling”, tried to focus on her values as a leader and on her work ethic, she said in an interview with the Guardian in June. “I prepared myself the best I could to get the job I’ve been striving to get for the last 16 years. Even if right now isn’t the right time. I have community support behind me.”

In his interview with the panel, Toller said he would bring what he described as necessary change to the elections office, and suggested he would not mind pushing back against state law.

“I’m a firm believer that just because the secretary of state of California tells us a statute or regulation must be interpreted in a certain way, that’s not the end of the story,” he said.

And then there was Curtis, who has advocated hand-counting and noted in his application he was a speaker at election events hosted by Mike Lindell, the MyPillow founder who has spent millions of dollars promoting lies about elections in the US.

During the public hearing in June, a group of residents who have frequently spoken publicly on their concerns about vote tampering and their beliefs that elections are being rigged expressed their support for Curtis. None of the speakers who offered public comment spoke in favor of Toller.

Still, Toller’s appointment was a win for critics of the elections office in a year with relatively few victories for them. Patrick Jones, the official who has most aggressively condemned voting machines and spread misinformation, in March lost his bid for re-election by a landslide. In June, a county judge dismissed a lawsuit from a failed supervisor candidate who sued the elections office, claiming that an error in the placement of her name on the ballot cost her the election. She had sought to change the outcome of the election.

“The lack of evidence was profound,” the judge said of the case. A state court denied her attempt to appeal the ruling.

Those who buy into conspiracy theories about voter fraud and stolen elections are not giving up on their efforts to remake the voting process in the region. The local elections commission recently recommended the county limit absentee ballots and return to one-day voting. Toller, in a move that may have surprised some of his supporters, rejected that idea and said doing so would not comply with state law. Those items will come before the board of supervisors for consideration.

With a new elections official, a deeply divided county and an intense presidential contest, the office faces busy and daunting months ahead.

Between November 2023 and June more than a third of the elections office’s 21 staffers left. But Francescut has said that she plans to stay put – at least through November – to help maintain stability in the office and support Toller as he learns the ropes.

“In the long run, ensuring that the November election is where it needs to be and the voters are able to vote, that’s the biggest priority right now in my mind,” she said. “It’s way more important than me as an individual.”