In my first year of high school, a girl called Barbara Diero and I were often mistaken for sisters. We had similar features: tall, slender and dark-skinned, with matching hairstyles. Both of us also bore the burden of sickle cell disease, which forged a deeper bond.

The disease manifested differently in each of us. Barbara suffered painful leg ulcers and slower speech and movement, while my symptoms were less conspicuous. “We will fight this,” I’d tell her, and she would smile her beautiful, infectious smile, which would become a cherished memory.

Sickle cell is the most common inherited haematological disorder in Kenya. It affects haemoglobin, the protein that carries oxygen in the body. Due to a genetic mutation, abnormal red blood cells become sickle-shaped and rigid, blocking small blood vessels and impairing blood flow, which then causes painful crises.

According to the World Health Organization, sickle cell disease affects nearly 100 million people worldwide. Each year more than 300,000 children are born with this disease, more than 70% in sub-Saharan Africa, though the disease also affects people with southern European, Middle Eastern, Asian, Latin American and Caribbean backgrounds.

Without routine newborn screening and access to proper treatment, more than half of those in sub-Saharan Africa die undiagnosed before reaching their fifth birthday.

Quick GuideA common condition

Show

The human toll of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is huge and rising. These illnesses end the lives of approximately 41 million of the 56 million people who die every year – and three quarters of them are in the developing world.

NCDs are simply that; unlike, say, a virus, you can’t catch them. Instead, they are caused by a combination of genetic, physiological, environmental and behavioural factors. The main types are cancers, chronic respiratory illnesses, diabetes and cardiovascular disease – heart attacks and stroke. Approximately 80% are preventable, and all are on the rise, spreading inexorably around the world as ageing populations and lifestyles pushed by economic growth and urbanisation make being unhealthy a global phenomenon.

NCDs, once seen as illnesses of the wealthy, now have a grip on the poor. Disease, disability and death are perfectly designed to create and widen inequality – and being poor makes it less likely you will be diagnosed accurately or treated.

Investment in tackling these common and chronic conditions that kill 71% of us is incredibly low, while the cost to families, economies and communities is staggeringly high.

In low-income countries NCDs – typically slow and debilitating illnesses – are seeing a fraction of the money needed being invested or donated. Attention remains focused on the threats from communicable diseases, yet cancer death rates have long sped past the death toll from malaria, TB and HIV/Aids combined.

'A common condition' is a Guardian series reporting on NCDs in the developing world: their prevalence, the solutions, the causes and consequences, telling the stories of people living with these illnesses.

Tracy McVeigh, editor

About 14,000 children are born in Kenya with sickle cell disease each year, the health ministry says. In rural areas, access to medical treatment is a challenge and often not the best quality.

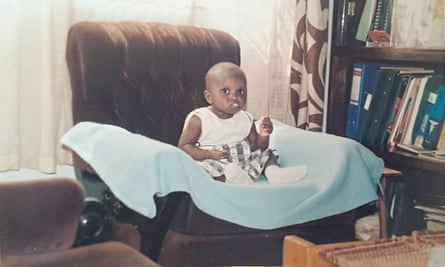

My medical life has been in two parts: pre-18 and post-18. My childhood was riddled with urgent visits to hospital. Having parents with medical insurance and living in Nairobi – where most of the best hospitals are – was a big plus. I had access to private hospitals and effective pain medication. With good city roads, the hospital was easily accessible.

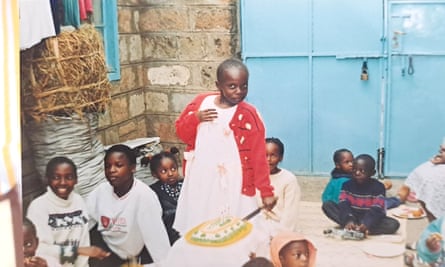

Before 18, diet was key. Pain crises break down the body – whenever pain strikes, you cannot use that body part for a week or two. To manage that, my diet – and in turn my family’s – had to change. We ate iron-rich foods, such as liver, beets and fish (not fried), complemented by daily consumption of porridge. Everything in my diet was traditional. Cheat days were on Saturdays, Christmas and birthdays.

After 18, managing the disease looked different. I knew my triggers and what level of pain equated to a hospital admission. The diet remained traditional, but with more cheat days. Now an adult, I could no longer use my parents’ insurance. I joined a university and the best thing was that it had a hospital. The downside was that I lost access to the fast-acting medication I’d had with the private hospitals.

Usually at the point of being admitted to hospital, the pain is a resounding 10, when zero means no pain and 10 means the worst possible. The medication I was now getting for level-10 pain was best suited for level 4. This meant I received several injections, intravenously and through a muscle, for relief. Exercise and supplements helped, but not always.

In 2014, my final year of university, I had the worst pain of my life. . Days after returning from the countryside, where we had stayed for Christmas, I fell ill. My eyes were rolling back and I was shivering, yet the sun was out: I had malaria. A double blow for a “sickler”, triggering severe pain and complicating recovery. It took a year to eradicate the malaria – it was a miracle I graduated.

This is where I debunked one of the many myths of the disease: that those with sickle cell cannot contract malaria. The myth almost cost me my life.

In managing sickle cell, I’m not the only one to discover modern medicine is just one piece of the puzzle. In 2021, a colleague’s four-year-old was diagnosed with it. The family tried to come to terms with the news, learning about the condition and finding routines to keep their child out of hospital. I talked to my colleague’s wife to understand how it is now for a child with the disease.

after newsletter promotion

“His last admission was in 2021. He is on medication, and diet has played an important role. I make sure he drinks a lot of water and stays hydrated. I also give him a lot of fruit and keep him on a traditional diet. I give him ndengu [mung beans], beans, kienyeji mboga [leafy vegetables], meat among others,” she said, adding: “Si unajua sickle cell yukula damu?” [You know sickle cell eats blood?] His blood level has improved.” The family is elated to have hacked sickle cell.

In 2022, I moved back to my family’s village near Homa Bay – AoraChuodho (“river mud”). When it rains, the only way to get to the main road is to walk through the mud with gumboots and it takes an hour to get there.

A few weeks after I relocated I got sick. I woke up early – pain has a thing for waking you up. I was in a foetal position. My knee was throbbing. The pain was in sync with my heartbeat, getting faster and louder.

I stayed curled up, it soothes me and eases the pain. This was a new experience. The sickness had never found me in this rural environment. The road was not too bad because it hadn’t rained the previous night so I was put on a motorcycle. The ride to the main road was 20 minutes.

At this point, I was unable to walk. The terrain wasn’t smooth and the pain got worse with every bump. At the main road, my father was waiting in his car. The hospital was an hour away. At this point, I couldn’t talk.

All I could focus on was the pain. When I got to the hospital they asked me my age. The nurse was shocked: “I have never seen a 30-year-old sickler,” she said. “In this area, they don’t survive past 18.”

I remembered that smile again: my friend Barbara – she died when we were in high school, forever pre-18.