There’s a pub near me in a town of a few hundred people. The building was more than a century old, the verandas were sagging and the patrons were sparse.

Two women saw its potential and took the surrounding country residents seriously enough to offer a good dining experience for a handsome price, confident we would pay for a decent meal in a beautifully restored building. It worked.

Every town has a similar story.

The pub restoration didn’t happen in a vacuum. It was next door to a great cafe that already drew people in, as well as a greengrocer and a wine shop. With the pub, critical mass was bedded down in a village of 300. Together, these businesses create a gentrified precinct.

You might know similar places, little pockets of caffeine-charged retail energy, that change the spending habits of locals and attract newcomers, some of whom move to the district permanently on the strength of the introduction.

It is hard to nail down what constitutes gentrification. Certainly, fancy pubs and strong coffee are staple businesses. More than half of Australia’s craft breweries and distilleries are now in regional Australia. Dog groomers may be associated with pampered inner-city pooches but they’re a dime a dozen in most country towns now.

While those local businesses are responding to the demands of existing residents, they have become important markers for the kind of towns that have attracted treechangers.

Surveying the regional landscape since the great regional migration in the Covid-19 pandemic, it’s not too much of a stretch to declare the country has developed its own kind of cool.

Over the past year, two studies (by the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (Ahuri) and the iMOVE Cooperative Research Centre) reveal that it was important to a portion of treechangers that their new community have an urban feel. Also important was proximity to the coast, a larger population centre and, most importantly, a job.

The independent economist Kim Houghton said the recent research showed that while regional migration trends were changing, 73% of people in capital city households remained interested in moving to a regional city, compared to just 57% of people in regional households being interested in moving to a capital city.

It’s the urban nature of a place like Ballarat in central Victoria that is an important attractor for people who cannot afford to live closer to the action in Melbourne. A bit of Brunswick in Ballarat, if you like.

Treechangers often came to regional cities via the stepping stones of brand new suburban developments in places like Hume or Whittlesea that are a long way from an inner-city vibe, but don’t feel too different to the outer suburbs.

“Ballarat has a gin distillery right in the middle of town so if that’s your jam, you could be within 10 minutes walk of it if you chose to,” Houghton said.

So four years after the start of the pandemic, the great regional migration is morphing again. People are more strategic about their desires and if they move to a place that doesn’t quite provide the services they need, they are not afraid to move on again.

Work arrangements remain the key to whether treechangers pick a city or country address.

after newsletter promotion

The data shows a very simple equation. If people have to go in to work every day, they prefer a regional city. If they have a hybrid office/home arrangement, they prefer a capital city. But if they can be fully remote, they again prefer a regional city.

But the hype about the work-from-home trend as a regional winner has not been fully realised. Consider companies such as Amazon which are trying to draw their workers back to the office, at the very least on a hybrid model.

Some of the most critical jobs on the ground in regional places are those that require workers to show up every day, such as childcare, healthcare and education. So that preference for living and working in a regional city if you have to make a daily commute might bode well for regional communities.

Finally, there was an idea that people would see the folly of their ways and, faced with lack of services and distance, would relocate back to a capital city. That is not borne out by the data.

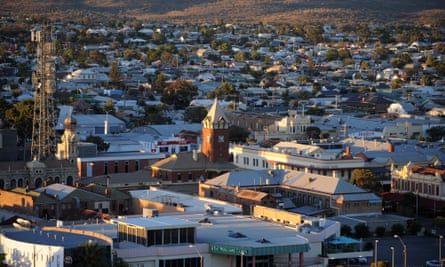

It is true to say, just because a place has attracted new residents, it doesn’t mean it will keep them. For example, the Ahuri research found that the likelihood of population churn was high across its case study areas of Port Macquarie, Ballarat and Broken Hill, with the highest number of survey respondents (44%) stating they were likely to move away in the next five years in Broken Hill.

But it is more likely they will move to another regional place, rather than back to the city. Survey respondents stated they would most likely move to other regional cities (46%) rather than capital cities (30%) if they were to move away from the case study areas, which is still counter to the overall urbanisation trend in Australia.

After years of trying to attract population, the biggest issue for local regional policymakers and planners is now anticipating population growth and the services, such as childcare, medical services and schools, needed to keep those new residents.

Small places will rise and fall but regional cities, especially coastal ones, will continue to grow if they have the conditions right. It would seem the regional renaissance is not over.

-

Dr Kim Houghton will host a free webinar on the latest trends in regional migration on 22 October

-

Join the Rural Network group on Facebook to be part of the community